Preface

Arrival and Iwakuni

Hiroshima

Kyoto

Tokyo

Afterwards

Preface

At the end of the winter of 2009, I went to Japan for two weeks. I had learned enough of the language to survive — numbers, courtesies, directions, basic grammar, and enough additional vocabulary to explain who I was and what I was doing there — though I was functionally illiterate, having learned the hiragana syllabary but no kanji worth speaking of. My ostensible purpose was to visit a friend and colleague who had recently taken up a professorship at the University of Tokyo, though I passed most of the trip in my own company.

I am about 180cm (6 feet) tall. I mention this as otherwise the reader might have the impression that I am a giant as I describe ducking through doorways and towering over the locals.

I have not tried to explain all the unfamiliar terms and foods. Wikipedia will tell you vastly more than I could. There are photographs of certain things where I believe them justified, with one exception: the Katsura Rikyu, where I simply did not have time both to marvel and to take pictures. Thankfully others have been less inhibited, and a quick search will turn up literally thousands of images of this treasure.

Y––– is a friend and colleague who worked with me in New York and later in Switzerland, and is now a professor at the University of Tokyo. My journey began at his family’s home in Iwakuni. From there I went to Hiroshima, Kyoto (where K–––, an American friend living in Japan, met me), and at last Tokyo.

Arrival and Iwakuni

2009-2-21

I arrived in Narita airport northwest of Tokyo after flying over Siberia, the most desolate place I have ever seen. It was snow-bound and hatched with frozen rivers, trees clustered along their banks and low mountains looming between them. I saw a peak-encircled lake, easily the size of Lac Yverdon, its surface solid white with ice. Occasionally I saw the straight line of a road, or a lone building in the snow. Aside from Siberia, I don’t remember the flight, thanks to some wonderful sleeping pills my doctor gave me.

Passport control took my picture and finger prints. Customs regarded me in disbelief for carrying a rucksack — half full of cheese and chocolate for my friend — for two weeks travel. I exchanged my Japan Rail pass, and ran for the platform to catch an express to Tokyo main station, where Y––– met me. We ate lunch in a tiny restaurant to the east of the station where my legs would not fit under the bar, but the pork ramen was excellent. Thus fortified, we caught the Shinkansen south to his family’s home in Iwakuni, near Hiroshima.

From the train, I saw the ocean in the distance. I caught a glimpse of Mt. Fuji, and watched the mountains rise sharp and wooded from the alluvial plains, and the sun set behind them. Y––– and I discussed mathematics. I dozed.

Y–––’s father fetched us in his van from Iwakuni station, and wound through streets I didn’t see in the dark to their family home, where Y–––’s mother was preparing a feast. I used their computer to email my parents,

Mama,

Im in Iwakuni (I cant find the apostrophe on the Japanese keyboard). Y–––s parents are absolutely wonderful, fed me a gorgeous dinner, and have been as kind as could be. Theyre going to take me around tomorrow to see the area.

Their house would make babo drool. Its a classic Japanese shop, with the corridor leading back from the street to the family area. Gorgeous woodwork, and I must admit I developed an immediate taste for tatami.

But the toilets in this country are so intimidating! They have lots of buttons and do crazy things…

Y–––’s parents are elementary school teachers, short and stout and utterly hospitable. Their English is about as strong as my Japanese. We communicated in a mixture of the two, and made Y––– translate anything complicated. They were slightly apprehensive about my visit, as I was the first foreign guest they had ever had. Their apprehension eased as Y–––, his father, and I sat on the tatami, feet tucked cozily in the heated space under a blanket draped table, then vanished as they watched in astonishment and gratification as I ate when Y–––’s mother summoned us to dinner.

Me with Y–––’s parents

I remember several kinds of sashimi. I remember oden, a rich soup laden with daikon, tofu, burdock, and more. I remember them bringing out a can of fugu filets for me to try. Unfortunately, I was so tired I didn’t write it down and the details have escaped me. Only the impression of wonderful tastes and good company remains.

After we had eaten, they invited me to take a bath. At this point, I must digress on the subject of a domestic institution which the Japanese have perfected: the bath. Y–––’s parents have an automated bath. They told a little machine to prepare my bath, and some time later it announced in a servile, feminine voice that it was ready. The rice maker did this as well, and they both startled me, much to the amusement of the family.

The Japanese bath consists of two rooms, one where you leave your clothes, and a second with a deep tub and a watertight floor. Y–––’s father had built a raise wooden floor to keep their feet from the cold tile, and I washed myself thoroughly on this before climbing into the hot water, maintained at a fixed temperature by the machine, to soak.

When I emerged at last, they showed me to my room upstairs. My circadian clock was completely adjusted to local time when I landed at Narita, but the length of my voyage had caught up with me, and I collapsed gratefully.

2009-2-22

Iwakuni occupies a river valley snaking among low, wooded hills. The Y–––’s family lives up a side valley lined with traditional Japanese merchant houses: deep, with the shop in front (converted in this Y–––’s home into a family shrine and interior garden, and a long passage next to it leading back to the house. Beyond is a backyard, and finally a stream channelled in concrete banks marking the start of the wooded hillside. I asked Y––– at one point who owned the hills. He says they are divided into pieces, each belonging to one house of the valley.

The family had retreated to one large downstairs room for the winter, containing the kitchen, a tatami space as a living room, and the small dining table looking out on the back yard and the deck Y–––’s father built. The rest of the house, the corridor from the front, the dining room dominated by a long wooden table, the bedrooms, were left cold for the winter.

My bedroom, upstairs, was a room around 6m long and 3m wide, with wood floors and a tatami at one end with my futon. It had been the children’s room before the all grew up and moved away. The bedrooms remain unheated during the day. In the evening I ducked through the doorway, turned on a heater and crawled quickly under the covers.

In my journal I wrote, “Woke up, wonderful futon with thick covers on tatami in upstairs room. Looked out at mountains behind the curtains. Breakfast at 9h: miso, rice, leftover stew (oden), plum pickles too strong for me, toast, scrambled eggs (green onions [are the] family’s special ingredient), daikon. Y–––’s father made the pickles.”

Y–––’s family proposed a tour of Iwakuni, lunch at a popular restaurant up in the hills, then north to Miyajima shrine. We came out into a cold, grey morning in their quiet street, no one stirring but two children riding one bicycle, and piled into their van, a twenty year old, smoothly functioning vehicle built for people smaller than me. Even in the front seat, my head was wedged against the roof. I argued forcefully with my subconscious as we drove into town. It insisted that we were on the wrong side of the street and were going to die until Y–––’s father dropped us off at one end of Iwakuni’s most beloved landmark, the Kintai-Kyo bridge.

The Kintai-Kyo is a series of intricate wooden arches, the obsession of a 17th century feudal lord determined to build a bridge across the river that would never wash away. [ticket from Kintai-Kyo] He came close, but it wasn’t adequately maintained during the second World War, and a typhoon destroyed it in 1950. The town immediately rebuilt it. Y–––’s mother seized the opportunity to photograph me contemplating the bridge, while Y–––’s father drove north to the modern traffic bridge to park on the other side.

Me looking over the Kintai-Kyo

The Kintai-Kyo connects the banks of the Nishiki river, the centerpiece of the several villages which merged to become the modern town of Iwakuni. Unfortunately the town doesn’t extend all the way to the nearby ocean. That part of the river is occupied by a US marine base.

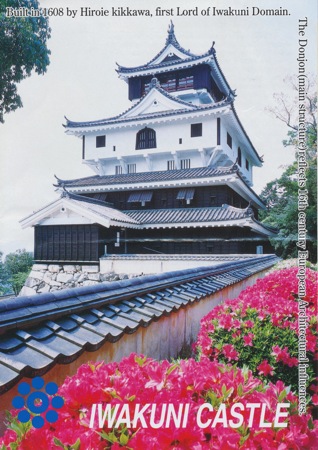

On the far side is a small park built around a statue of Hiroyoshi Kikkawa, a one-time lord of the town. Around it are the old residences of the samurai who lived here, tile-roofed houses and outbuildings surrounded by low walls. The grandest of them is now occupied by the principal of the local school. Beyond lies Kikko Park, a maze of concrete and stone walkways among pools, fountains, and flower beds built on the site of the Kikkawa family’s residence. Most of the town’s public parking lies just beyond Kikko Park, in a gravel lot surrounded by the white snake museum, the art museum, the funicular up to Iwakuni castle, and a pair of old cars converted to burn charcoal and left there as museum pieces.

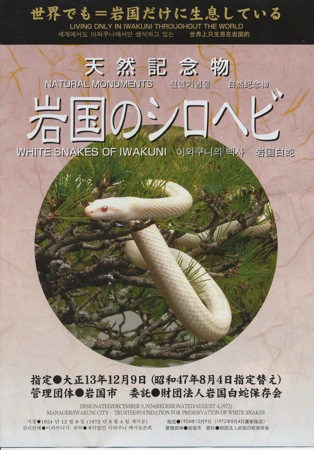

The white snake museum is a single room housing a large terrarium, home to several examples of a unique strain of poisonous, albino snake indigenous to the region. The staff were very excited to give me an English language pamphlet. Essentially every museum in Japan has an English language pamphlet, no matter how small and off the beaten track it is, usually full of lovely photographs and endearing misuses of English.

Brochures from museums in Iwakuni

We didn’t linger –– Y–––’s mother hates snakes –– and took the funicular up the hill, then would along a forest path to Iwakuni castle at the very top. The castle is a reconstruction begun during the post-second World War epidemic of castle rebuilding in Japan. The original had been torn down 1615 because the lord of Iwakuni, when told by the shogun to decide between his castle and his manor in town had sensibly chosen the latter. It displays some tiles used for the eaves and decoration of the roof, pictures of the Kintai-Kyo and various other bridges, and an enormous collection of swords, the first of many I would endure on this trip. The Japanese find themselves in possession of an enormous number of ornamental swords which no one particularly wants, so they use the large number of reconstructed castles, which no one has any particular use for, to display them.

Finally we reached the real reason to visit the castle, the view from the top, and gazed out on the snaking Nishiki among the hills, the irregular patches of village along the river valley, the shinkansen line cutting across the landscape, and the sea in the distance, and the mist gathering over it all. There were two other Americans and their small child admiring the view at the same time who will put in an appearance again.

We took another path down to the funicular, winding around the far side of the ridge, and past an old well overhung by a pair of gnarled, ancient trees twined one around the other, and watched children running in joy around a musical clock as it chimed the hour while we waited for the cable car down.

There is a facial structure that occurs among Japanese women that is strikingly beautiful. The Japanese tend to have strong jawlines, to the point where some of the faces are practically perfect ellipses. Often the long eyes, a wide mouth, a small and slightly hooked nose go with this shape, and the effect is stunning. I saw it twice today around the funicular, once on a young lady waiting to descend, and at the bottom on a mother maneuvering her stroller in position to ascend.

At the top I had noted a garden with wooden buildings in it, that I was told was a Shinto shrine. As we descended, Y––– explained to that each family belongs to one of the Shinto gods, and we walked east to the little shrine nestled just inside the woods where his family makes their devotions. Y––– explained the ritual to me: walk up to the shrine, drop a small coin, say ¥5, in the grilled box, ring the bell with the wide, braided rope that hangs there, then bow twice, clap twice, and bow twice more. We paid our respects to the god, and then they showed me another source of income for the shrine: horoscopes.

Near the bell and grill is a box filled with folded pieces of paper, for sale for something like ¥100, offering advice on work, school, relationships, weather, and the overall outlook of your luck. Y––– explained that the Japanese want to get the horoscope predicting decent luck, not the best luck, because from the best it can only get worse.

The horoscope from the shrine

The gathering mists had become clouds and begun to rain. We piled back into their van and drove up into the hills to a restaurant called the “Bandit’s Nest,” a collection of low, traditional buildings with giant signs nestled in a corner of the mountainside. We left Y–––’s father to find a parking spot amid the crowds of people who had come out for lunch in the country, and entered through an alleyway between low eaves, lined with quantities of sweets, snacks, and small toys for sale by women in a romanticized impression of bandit clothing: dark, simple robes, grey head cloths, grey socks and wooden sandals.

Waitresses ran around in confusion for a moment, then we were shown to a raised wood floor with enclosed by paper screens, and a long, low wooden table. I tried to sit cross legged like the rest, but my knees simply would not fit under the table. Y––– and I compared the angle of our legs. Mine were as flat as his, just much longer. In the end I alternated kneeling and sitting cross legged back from the table.

Everyone who comes to the Bandit’s Nest orders the special, it seems, including us: a leg and thigh of chicken teriyaki on a skewer, a bowl of udon in broth, and a rice ball with pickles at the center. The food arrived, the waitress paused, looking at Y–––’s father, then cried, “W–––-sensei!” Her son apparently attends the school where Y–––’s father works.

I attempted to manage the chicken with my chopsticks for a couple minutes, then gave up and declared to Y–––, “I’m going to be a gaijin and use my hands,” to which he replied, “I follow.” This appeared to be the normal progression not only for us but for all the families at the tables around us.

The waitress returned afterwards with a gift of dessert: warm, sweet red bean broth with glutinous rice balls, chewy white spheres about a centimeter and a half in diameter which soak up the flavor of everything around them.

The food was excellent, but I was simply too large for the place. The merchandise-lined entrance forced me to bend almost double. At one point I walked into the edge of a roof full force, leading Y–––’s mother to solicitously and profusely apologize while I assured her that I hitting my head on things has never been much of a concern for me.

After sating ourselves on warm soup and chicken, we set out north for Itsukushima to take the ferry to Miyajima. I promptly fell asleep during the drive.

Miyajima is a town on a mountainous barrier island separating the sound in front of Itsukushima on the mainland from the Pacific Ocean. It faces the sound, and so does what everyone comes to see: the shrine of the sea god, and its great gate on the water.

The great gate at Miyajima

We joined the crowds boarding the ferry. We walked through the shopping streets of Miyajima. We admired the pygmy deer that wander freely and fearlessly through the town, occasionally blocking traffic with utter aplomb. And we arrived at the shrine.

Miyajima shrine is built on stilts over a tidal flat. At high tide you can approach through the great gate to the shrine itself in a small boat. We came at low tide, and after contemplating the great gate for a few moments, I led Y––– out onto the mud to get a better luck.

Me gazing on the gate

The gates to all Shinto shrines share a form: two uprights, often with transverse braces, leading to a pair of crosspieces which form the top of the gate. The lower crosspiece is straight and slightly longer; the upper is curved up, but the exact curve varies. Miyajima’s gate is painted the vermillion that the Japanese favor for their temples, which glowed against the backdrop of grey sound and grey sky, but it was the top crosspiece which took my breath away, a curve with all the projective illusion of Rodin’s best sculpture, giving an impression of a boat hull from all views, but a boat continually changing: here a dory, here a great longship, here a modest rowing craft somehow perched atop two giant pillars.

Y–––’s parents indulgently waited while I contemplated the wonder of this curve, doubtless wondering about the sanity of the American who wanted to go see the white snakes, was staring at one piece of a gate, and had expressed great enthusiasm for the idea of going to the local grocery store, then led the way into the shrine itself.

In most shrines the buildings sit in a small park which takes some elements of the Japanese garden in its layout, and which is as much a part of the shrine as the buildings themselves. Miyajima’s park is the water on which is floats at high tide, or the mud at low tide, and covered walkways, expanses of wood planks edged by white latticework and vermillion pillars. The buildings themselves extend seamlessly from the walkways, here the main hall with its expanse of shining wood floor between vermillion columns, there the storage house for the god’s sake casks.

We finished and found a café in Miyajima’s shopping district to have tea and a snack to cast off the chill of the day. The café in Japan has a collection of elements as fixed as the café in France, but completely distinct: benches draped with red cloth with serve as both table and chair, hovering waitresses who welcome you, and bring your order and set it on your bench. We gratefully received our green tea and local pastries, leaf shaped and soft and filled with red bean paste or green tea paste or an assortment of other things, enjoyed the warmth of the shop, and browsed the tacky items for sale, for it was first and foremost a souvenir shop.

Miyajima’s shopping district is strictly for tourists, yet is not vulgar. If you stop for food, it is decent. There are no enormous neon signs. The people working in the shops lack the jaded edge of those in tourist traps in America. We peered in other shops, and Y––– stopped –– at his mother’s insistence –– to buy sweets to take back to his wife in Tokyo. This led me to tell a joke whose origin I have long forgotten: a professor of mathematics gave his graduate student a birthday present. The student’s wife beleaguered him until he wrote a thank you note, which he took to his professor, saying, “I’m sorry this is so late.” The professor’s response was, “Oh, don’t worry about. It was my wife who told me I had to get you a present.”

We took the ferry back across, after pausing so Y––– could join a crowd of Japanese schoolgirls taking pictures with their mobile phones of three cold, wet deer huddled under a sign (he claimed it was for his wife), and went to the grocery store!

I think they didn’t understand my enthusiasm for the grocery store, and kept saying that if I saw anything I really wanted to try, just to say so. But it’s not to try particular things that I wanted to see at the grocery store. In a developed society, the grocery store is one of the central institutions that defines how people live. The local grocery store is a window on the nation.

Japanese grocery stores have exquisite fish, as you might imagine, available as whole fish, filets, or sliced into sashimi. Fruit is of the same high quality available in Europe, but vastly more expensive. On the whole, the selection is weighted much more to partially prepared foods and processed ingredients than in the Europe, more even than in the United States. Miso, for instance, was sold by the same companies in similar packaging as raw miso in its various colors and grades; as miso mixed with dashi1 ready to mix with vegetables and boil into soup; and with the vegetables already added, requiring only addition of water to the thick paste. It’s as if instant roman were sold with the same quality and aplomb as bouillon.

I must make a further comment on miso: Ezra Pound’s obsession with pictorial representation in Chinese characters is rubbish. Careful examination of

噌,

the second character in “miso” (味噌) suggested to me a horse watching television. Y––– pointed out that it is a house beyond a rice patty with the sun shining on it from the left, and in a clean font such as the one above, this is visible, but in the more stylized writing on the packages, I maintain that my horse was far more plausible.

After checking out, I made my acquaintance with the other thing in Japan, along with talking household appliances, that continued to astonish me as long as I was there: hot drinks from vending machines. You put your coins into the machine, and it produces a bottle containing hot tea, hot coffee, even hot chocolate. This is actually far more astonishing in person than to describe. The quality isn’t magnificent, but perfectly drinkable.

We dashed through the rain to their van and drove home, where Y–––, his father, and I installed our feet under the heated table in the living room while Y–––’s mother prepared dinner. I tried to offer to help, but was very kindly told to go sit down. While she cooked, we watched a Japanese nature show, entitled “Darwin has come!”, on sailfish. It was an impressive piece of work, featuring breathtaking underwater photography of groups of sailfish working schools of fish, careful explanations of what they were doing, of the hydrodynamics of various body shapes of fish, and even some delightful footage of a baby sailfish, which had not yet grown into its hydrodynamic form.

Y–––’s mother called us to the table. I wrote of this meal, “Dinner: oden (stew cooked on table) of beef, chicken, pork, gobo, tofu, daikon, mushrooms, green onions; sashimi, sea cucumber, kim chi, and apples for dessert.” She kept reloading the metal pot on its burner in the center of the table whenever we seemed in danger of making a dent in its contents.

I availed myself once more of the bath, then Y–––’s mother made matcha, the strong green tea of the Japanese tea ceremony, for me, though thankfully omitted the ceremony at that hour of the night. Y––– and his father had been drinking sake and so wouldn’t have any, but we all had some normal green tea afterwards, then crawled off to bed after watching some of Japan’s numerous and very strange game shows.

Hiroshima

Monday, February 23, I wrote in my notes, “Slept ill, kept thinking about math and watching the predawn light over the mountains. Breakfast much smaller this morning: miso, toast, apple juice, strawberries, rice, seaweed, pickled tuna.” Y–––’s father dropped Y––– and me at the train station where we stared at the mist on the hills until the train to Hiroshima arrived.

Y––– continued on to Tokyo. I spent my first day following the itinerary of Hiroshima’s sights recommended to me by the little old lady who runs Ryokan Sansui, where I was staying on the southwest edge of town. I left my pack there, and, after she had taken my photograph in front of the inn to add to her wall of other guests, I started along the path to the Peace Park, the A-bomb dome, and up to Hiroshima castle.

Me in front of the inn in Hiroshima

Hiroshima lies in a river delta. The Peace Park lies in a fork of the river which was the old merchants’ quarter, and the epicenter of the atomic bomb blast. A white stone conference center dominates its south end, with free public Internet access — but not today, as it was surrounded by riot police in black armor. I skirted them, walked past the cenotaph and the flame which the city says will burn until the last nuclear weapon is dismantled and past a display of thousands of origami cranes folded and brought by schoolchildren around the world in memory of a child who had folded endless numbers of them while dying of radiation poisoning. Despite its displays, the park is a happy place, full of locals strolling and children playing on the grass.

Somewhat less happy is the A-bomb dome, the remnants of a steel and concrete building that was directly under the explosion. The locals walk past it with barely a glance, but here I saw the only other white faces I encountered in the course of the day, frame packs strapped to their backs and guidebooks open.

Hiroshima has very cleverly managed what tourists they do receive. All the memorials are concentrated in the Peace Park at the center of the city. Most tourists arrive at the train station, take the street car to the park — it’s the only stop announced in English — wander around and beat their breast a little, then return to the train station and depart. This leaves the rest of the city as a playground for the locals.

I bought lunch from the food shops in the basement of a department store on the Kamiya-cho, the main east-west street which cuts from the rail station through the city, ate it by the river at the north end of the park, then walked north to Hiroshima castle.

Hiroshima castle is a stone foundation surrounded by a moat, a great square except for the rectangle of the donjon protruding to the south. Most of the interior is scattered with the foundations of old buildings amid a few trees, but certain parts of it have been reconstructed.

The donjon has its wooden walls and gates, and the long corridor of gleaming wood on its south side (leave your shoes at the door and take a pair of slippers from the rack). A Shinto shrine stands on what was the military headquarters during the war, where high school girls working as radio operators cobbled together equipment to send out the first distress signal after the bombing. At the far northwest is the second reconstruction of the castle’s tower. The city built a temporary tower for a large exposition, and tore it down afterwards, but the locals decided they liked having a tower and the current one was put up as a museum.

The museum recounts the history of the city and the castle, the city by fairly conventional means (maps and text and dioramas giving an image of daily life), the castle told aloud by a holographic projection of a cartoon ninja sporting an enormous nose as he hops around a model of the castle. Then there is the necessary collection of swords, and while I was there a special exhibition on Noh dance. The masks were interesting, but the video of the dance was frankly rather boring. Finally, the top floor is an observation deck, just like in Iwakuni castle. The city has grown too tall to get a really spectacular view, but I was treated to the sight of a man and women in traditional garb being photographed in baseball advertisements in front of the castle, imitating a batter’s stance with their wooden umbrellas.

I had done enough for one day, and went back to rest in my room until I went out for dinner at Sanshuin, a restaurant recommended by my idiosyncratic guidebook. I found it on my map. I navigated to exactly that point, and then I was stuck. I couldn’t read any of the signs around me.

Indeed, the single most frustrating thing about Japan and the Japanese is their absurd writing system, made up of the Han characters of Chinese, a system formulated to be hard to learn and hard to use, mixed with bits and pieces of two phonetic syllabaries — they are not alphabets, as they don’t separate consonants from vowels and can so represent only a small, fixed number of syllables. The system is so inefficient that Japanese graduate high school having not yet acquired enough characters to read their own literature.

Chinese keeps its characters because switching to an alphabet would require admitting that Chinese is a family of languages as diverse as the Romance languages, which for political reasons is apparently impossible. None of the languages that make up Chinese fit well into any of extant alphabets, and the cost of teaching everyone the new system would be prohibitive.

Japanese has no such excuse. It is a single language. It has even fewer sounds than Italian or Spanish, and can be written phonetically in the Latin alphabet with no exceptions. Most importantly, every Japanese studies at least some English in school, so they can all read the Latin alphabet. Turkey switched to the Latin alphabet in the space of a week, with none of these advantages.

As I looked around in frustration, a young lady stopped and asked if she could help me, then pointed to the entrance next to me and told me that it was Sanshuin.

The staff in kimonos greeted me, I was shown to a table in an interior of polished wood and paper screens, and an old lady who stood eye to eye with me when I was sitting brought me an English menu, then told me in Japanese what I was to eat: a soup cooked on the table laden with rice, vegetables, and the oysters for which Hiroshima is famous. She brought it out and gave me careful instructions to let it cook for thirty minutes, which I misheard as three. Three minutes later she came rushing over to bat my hand away from the pot as I opened it to serve myself.

It was delicious, but like so much in Japan had very little smell. To someone used to the heavy aromas of Italian cooking this is very peculiar. I sat and digested for a little while, then paid my bill of ¥840 and exchanged many bows with the staff as I left.

2009-2-24

I finished my tour of Hiroshima’s well known sights the next morning when I arrived in a light rain at Shukkeien garden. The garden is organized around a central pond with the villa of the garden’s original owner sitting on its south shore. Paths wind around the pond, off to the west to the plum orchard in full blossom, up onto a little wooded hill and beyond to a sward along the river, and up a miniature mountain to the northeast and down into a bamboo forest on the far side.

By their nature Japanese gardens are games of perceived scale, trying to cram a miniature landscape into a closed world like a ship in a bottle. The good ones play with this fact, and within meters your perception changes from that of an ant staring up from the grass to that of a titan bestriding a hilltop and staring out to sea.

The garden was empty when I arrived but for a few groundskeepers and a cormorant fighting with an eel in the pond. A few small groups of elderly Japanese drifted in to brave the rain, and the cormorant caught the eel and began swallowing it whole. By the time I left it had filled its belly, but still had a throat full of eel and ten centimeters of the tail protruding from its beek. It swallowed desperately, perched on a rock, and looked truly miserable.

The chill and damp of the morning drove me at last to the tea house at the southwest corner of the garden. The young lady working there greeted me and ensconced me on one of the benches draped in red cloth next to an old Japanese man. The old man and I grunted agreeably at each other until the lady returned with my macha tea and a sweet of red bean paste coating a glutinous rice ball. An older lady appeared from the kitchen to watch me drink the tea, and I was told she was the younger’s instructor in the art of the tea ceremony, visiting that day, and had prepared my tea. Then the ladies proceeded to extract my story: that I was an American physicist living in Switzerland, my itinerary in Japan, my age (”so young!” they cried when they found I was 25), and discussed it carefully with the old man, who it turns out was a kendo instructor who had competed in New York City once upon a time. Their attentions continued until the old man’s wife came to claim him, and I felt warm enough to return to the garden.

After one more turn through the garden, I walked south in search of my lunch until my instincts pricked at a fast food restaurant full of clerks, construction workers, and security guards. I queued, examined the menu, which thankfully had pictures, and managed to place my order and pay my ¥500 without delaying the line. I stood to the side awaiting my food and listening to the nasal, high pitched singsong of ultra formal Japanese which women use to customers in this country, then carried off my tray of beef and vegetables over rice, a small bowl of pickles, and a big bowl of red miso soup with pork to a seat by the wall.

As I left my inn to go to the gardens that morning, the innkeeper had given me a ticket to an ikebana (flower arranging) exhibition at one of Hiroshima’s big department stores, Fukuya. To a Westerner, the idea of an exhibition at a department store sounds odd, but Japanese department stores follow a different model: one or two levels of food, both raw and prepared, in the basement, a level of luxury goods like perfumes and jewelry, a level of women’s clothing, a level of men’s clothing, a couple levels of housewares, linens, and paper goods, and, on the top level, art galleries and exhibition halls. The stores sell paintings, pottery, and sculpture by local artists and craftsmen, and provide space for shows. There are exceptions, such as the chain of giant hobby stores Tokyu Hands, but even the way it arranges its goods recalls the general department store.

I was so much taller than most of the people in the exhibit that I could stand in the back and see over everyone without difficulty. Unfortunately, ikebana is horrendously boring and artificial. Exactly one piece had some artistic content, an group of plum boughs arranged back to front, going from bare winter branch at the back to full blossom at the front, kind of an allegory of the seasons. I believe it was due to statistical chance, as I saw all other permutations of the same material in the same kind of vase from other exhibitors. One of them randomly managed to order it correctly.

I glowered my way through the exhibit until my twisted brain suddenly suggested looking at the arrangements as aliens. Instantly I had to contain my laughter at old ladies nodding sagely at tentacles and eyestalks reclining on alien furniture. Yet even this did not salvage the whole show: a few pieces would not even resolve themselves into aliens for my amusement.

I escaped to the far more artistically interesting housewares section. Each department store has its own brands and suppliers, its own designers, and so their own designs for bowls and dishes. Some are mediocre, a few are downright ugly, and among them are a surprising number which are works of art in their own right.

I went south from Fukuya into the covered pedestrian street at the center of Hachobori, Hiroshima’s shopping district. In the evenings the laughter of people promenading and the cries of shopkeepers echo down the long passage of white paving stones and arched roof. I was here to buy a camera, a resolve that had taken me in my last turn around the Shukkeien garden.

I had never owned a personal camera before, though I had worked with powerful cameras attached to microscopes in my research. I preferred all these years to keep meticulous written records my travels, and I still do. The camera requires too much attention. It changes the way you look at the world. But so much in Japan asked me to look at it in exactly that way that it seemed a reasonable possession.

I went into Deodeo, the most impressive electronics store I saw in Japan. On the first floor that opens on the mall it looked like a fancy camera shop, but start taking the elevators up and there were enough bins of computer parts, and the latest gadgets, connectors, and dongles to make me feel like a country bumpkin.

I looked over the cameras, and when a sales clerk asked if she could help me, I told her that yes, she could. Thankfully she spoke decent English, as my Japanese was not up to the task, and she had me sit down at a table in the corner while she ran around checking the compatibility of memory cards and finding the right color. The Japanese have made customer service into a high art, to the point where even I can enjoy shopping, though I still feel slightly embarrassed at their attentiveness.

After a rest in my room, and setting the new camera to charge, I went out to find dinner. At last I stumbled across a little place called Sakagura, walked in, and was greeted by a young waitress who looked up and up at me, bowed nervously, and asked me to place my shoes in a locker by the door.

The restaurant consisted of tables in booths to the right and a sunken bar across from the chefs to the left, separated by a wood and bamboo partition. She placed me at the bar, where I managed to find space for my knees, and brought me tea and a menu.

The staff were not used to foreigners, but quickly went from nervousness to delight when I demonstrated that I could eat, I just couldn’t read. They were young, the oldest being the twenty eight year old cook grilling skewers across from me, or so I was informed by the waitress who had let me in, and who took a shine to me to the point where I thought she was going to take me home. When she had a moment to spare, and they weren’t that busy, she kneeled by my seat and in a combination of Japanese and a few words of English extracted even more detail than the ladies at Shukkeien garden’s tea house, also finding that I am a violinist and speak French, and again the waitresses chorused “So young!” when they learned my age. In return I learned that she was 23, loves J-pop — she ran to fetch her phone to show me a picture of her favorite band, a group called TMR — and draws. Throughout this the cook across from me kept chiming in with totally inappropriate comments which made her laugh and blush, and occasionally threaten to hit him. The other staff paused in interest when they had time, and by the end of the meal I had three waitresses and two cooks gathered around me asking about Switzerland, French, and what I thought of Japan.

Young they might be, but they could cook. I started with a piece of octopus sashimi, then salmon sushi, a piece of omelette sushi, a pile of breaded and fried things whose names no one knew how to translate, chewy and crunchy skewers of chicken parts (legs, hearts, and livers), and for dessert a white custard with fruit served on a container of dry ice. After that they gave me a cup of hu, a roasted brown tea, and when at last I rose to take my leave my waitress, who had been tending to a table in the other corridor, ran to exchange bows and smiles and goodbyes with me as I left. Naturally I loved the attention.

2009-2-25

The next morning I returned to Shukkeien garden with my camera. Photographing a Japanese garden is actually rather simple. In traditional gardens, the stones are carefully placed. The have a purpose. This one is part of the edging of a path, that one frames a streamlet, this boulder coyly blocks part of the view across the pond at this point. But there are a few without any obvious structural purpose. They’re view points, and sometimes pointed in case you are too dim to figure out which vista you should be looking at. I tried photographing from other places, but results from these stones were so much better that I soon gave up. Benches in the garden are for resting. They don’t have frames vistas, but are secluded, a place to rest your eyes as well as your feet. The pavilions are placed to give panoramas, and when I finished photographing the garden, I retired to the southern pavilion, left my shoes beyond the edge of its wood floor, and settled down to relax for a much needed rest.

A little old Japanese man, dapper in his tweed suit and flat cap, found me there and was astonished that I was kneeling like a Japanese. He admired my very poor Japanese, asked how long I had been in the country, and politely passed the time of day for several minutes.

The garden, arranged in order as if walking around the pond starting on the left:

|

| Shukkeien gardens, Hiroshima |

As I left the garden, I ran into the American couple I had seen at Iwakuni castle, and introduced myself. Deb and John, and their two year old child in the stroller, were visiting from Virginia Beach. John was in the US Army, and they were staying at the marine base near Iwakuni. But it was not military business that brought them here. John judged “Magic: The Gathering”2 tournaments in his spare time, and had been flown over to be a judge for a big tournament in Kyoto. They were on their way to Hiroshima castle, and I guided them to the east entrance while we had a nice chat, then left them and went in search of my lunch.

Just north of the covered shopping street, I found a tiny tempura restaurant: six seats at the bar, six more around a communal table on a raised tatami in the back. The waitress put me at the table in back, gave me a menu, and told me what to have, which was the same thing everyone else in the restaurant was having: tempura of shrimp, oysters, tiny, whole fish, and clusters of mushrooms over rice, a bowl of miso soup, shredded daikon to mix with soy sauce for the tempura, and a cup to pour myself hu from the communal pitchers on the table.

While she was bringing this, I examined my table mates. Two were businessmen in their fifties, their ties loosened, one with his coat off, attacking their tempura with a gusto wonderful to see. The other two were young, not much older than me, and both wearing the carefully tailored and immaculate suits. The man was here from Kanto to visit the woman, and they passed their time talking about work and bosses and showing each other pictures on their phones.

I ate with as much gusto as the businessmen, paid my ¥900, and walked across the street to the Anderson Royal Danish Baking Academy. Its ground floor is a bakery and delicatessen. The second floor serves hot desserts, but I never made it past the pastry below. I took my tray and pair of tongs, and snagged dainties before presenting myself to the cashier, who carefully wrapped up my goodies, including a red bean croissant, an exact analogue of a chocolate croissant but with red bean paste in the middle. I have no idea why there is such an institution in Hiroshima, but their pastry was heaven sent for an American used to a sweet at the end of a meal, and who had finished the last of his Swiss chocolate the day before.

From here I walked southeast, through the red light district getting ready for the evening, then through quiet, someone dilapidated residential districts until I crossed another branch of the river and started climbing up into Hijiyama park.

Hijiyama park is everything the Peace Park and Hachobori are not. They are all concrete and tended lawns; it is wooded and wild. They are alive with people and activity; Hijiyama is a retreat for the people of the city. When the atomic bomb hit, Hijiyama is where the people fled. I climbed past a temple, past the great white angles of the Museum of Contemporary Art hidden in the forest, paused to peek in the city’s manga library and stroll around its adjoining gravel terrace, and climbed up to the Radiation Effects Research Organization, housed in prefabricated 1960s laboratory space at the top of the hill.

Hijiyama is full of cats, not precisely feral, though they do not have owners. They are “public” cats, providing the living side of this retreat from the city, and figure in all the hill’s drama: a child, running towards a cat and crying, “Mommy! Look! Meow-meow!”; a taxi driver, his shining vehicle parked on the grass, carefully using chopsticks to set bits of fish from a plastic bag in front of several cats; settled on a bench at an overlook, a melancholy man with a cat purring on his lap which he urges to look into his camera phone to be photographed; a fuzzy wiener dog running around trying to make friends with a group of cats, and failing miserably while his owner giggles.

The same dog sniffed my hand, decided that I was simply too big for comfort despite the fact that I was squatting, and scuttled away. I have this effect on most Japanese dogs.

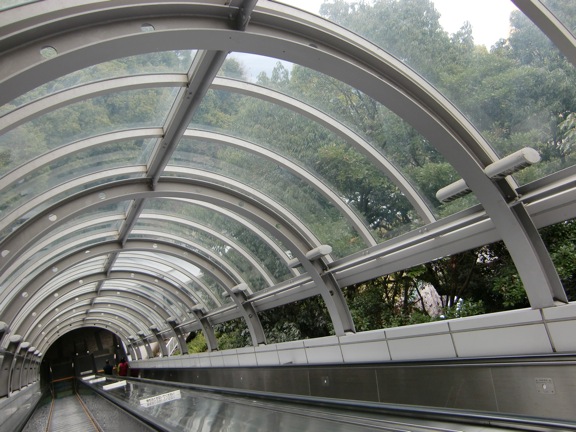

On the east side of the park is one of the more interesting technical artifacts of the city, the Hiroshima Sky Walk.

It’s a giant, covered escalator leading from SATY, a Wal-Mart like department store at the base of Hijiyama, through the woods, to the road at the top of the hill.

At last I descended, bought some food to have dinner in my room, and went back to the inn. I ducked the 10cm to pass through the doorway of my room, changed into my yukata3, made tea with the pot and utensils provided, and lounged on the tatami.

It wasn’t a large room –– 4 tatami in area, with my futon folded in one corner, a low table, a heater, and a big window looking out on a tiny courtyard –– but spotlessly clean like the rest of the inn.

The next morning was my last in Hiroshima. I was watched by a cowering, horrified black pug while I practiced kung fu by the river, and wondered again what is wrong with Japanese dogs, then took my camera back to the redlight district southeast of Hachobori to capture it’s rather intriguing street art.

The district was empty besides a few people cleaning up after last night, and me, as I moved bicycles and signs to get clear shots of the paintings, then carefully replaced them.

Finally I went into the A-bomb museum, which I had omitted on the first day. It is a very moving, well done museum, uninterested in vilification, only in explanation. It traces Hiroshima’s development through the 20th century with a mass of really fascinating photographs, then there follows a disturbing look at the effects of the atomic bomb, and the immediate aftermath. From there, I caught the streetcar back to the station to take the shinkansen to Kyoto.

Kyoto

2009-2-26

I arrived in Kyoto on the Shinkansen in the mid-afternoon, thoroughly bemused at the strict gender roles on Japan Rail: each car is tended by a lady in bright clothing of her choice, with a cart of food and beverages. The conductors are male, in strict uniform. Even the cleaners who swarm into the trains at terminus stations have color coded uniforms — blue for men, pink for women — and have one of each ready to enter each door.

My friend K––– has been living in Japan for the last year or so, teaching English, and she agreed to come visit Kyoto with me. I checked into our inn, the Ryokan Shimizu not far from the train station, drank the cup of yuzu4 tea they brought me, and left a note in the room: “Gone walkabout, will call ryokan if arrested.” I wandered through the nearby area, thinking about the evolution of prisoner’s dilemma strategies and its relation to nuclear disarmament — the museum in Hiroshima this morning was still much on my mind.

Shimizu is in an old part of town, a mix of recent, four story apartment buildings, and old, one story shops, all on streets so narrow that only one car at a time can pass, if it all. It’s not a young neighborhood. Most of the shops were run and frequented by the elderly. I strolled east to the walls of Nishi Honganji, an enormous Buddhist temple, west to a highway, north to another, and circled back around to arrive in the room around 16h30, when K–––’s train was supposed to reach Kyoto. I walked in just as a young lady of the hotel staff was delivering a cup of tea to my newly arrived friend.

Shimizu is definitely the nicest place I stayed in Japan. You leave your shoes at the entrance to the inn, step up onto the polished, wooden floor and put on a pair of slippers. Our room opened off the upstairs hallway. You open the door and leave your slippers in the entranceway, stepping up in your socks onto the even more polished wood of a private hallway, containing the sink, the doors to the toilet and the bath, and sliding doors opening onto the tatami of the bedroom. K––– and I sprawled on our futons here and talked for a couple hours before going in search of dinner.

A block or so north we found an okonomiyaki restaurant run by a middle aged couple, consisting of a bar with six places and a table with four chairs crammed into a hole in the wall. K––– ordered us green tea and an okonomiyaki with squid and shrimp. The man spread his flat griddle with lard, and mixed the ingredients to fry, then added little clusters of mushrooms when he saw K–––’s eyes light up at the sight of them.

It was excellent, but we wanted to see more of the area, so we paid and moved on to a larger restaurant with plastic food in the window, where I ate soba in soup with a herring on top, and K––– had cold soba with a dipping sauce of soy sauce, wasabi, and green onions. At this point she was exhausted, as she usually goes to bed very early, so we retired for the night.

2009-2-27

We compromised between my normal hour of 7h00 and K–––’s pathological 3h30, and woke this morning at 5h00 to see Nishi Honganji in the dawn rain. The wooden floors were freezing, the complex swathed in scaffolding and mostly closed. So was the next temple we visited, though we admired the painted lions cavorting on the gate. There followed Chisakuin temple, also closed, but where we could gaze into the hall with its great, gnarled timbers as roof beams. It was here that we met an old Scottish couple seeing the sights. K––– went over the map with the lady, giving directions. The man and I stepped aside and had a lovely conversation about sailboats, for it happened that they lived part of the year on their boat in the north of Scotland, and his work before he retired of designing steam turbines for nuclear reactors and supertankers. They were leaving that evening, unfortunately, or we would have met up for dinner.

The next temple was open: Kiyomizu-dera, a place mobbed by the Japanese every spring to view the cherry blossoms. We climbed through the narrow streets leading to it, past rickshaw drivers in headcoths and two-toed sandals, past small shops and expensive homes, past an English cottage on stilts with its roof almost touching a corner of the temple. At last we mounted the stone steps to the gate flanked by its huge stone guardians, their hands raised, their faces furious, to see a panorama of great vermillion and white buildings against green mountains and grey sky. The general scheme is fixed throughout Japan: the beams painted vermillion, the panels between them in white. It’s the details of the decoration that vary. In one pavilion overlooking the city the beams ended in the carved heads of crazed looking elephants. The panels of the bell tower bore multicolored painted chrysanthemums.

We cleansed our hands in the fountain5 and ascended to the main building, an enormous black and white structure in wood cantilevered off the mountainside, then followed the contour of the hill past more pavilions. The path is enclosed by sakura orchards and forest above, and a stream among dense greenery below. We avoided getting in line to drink from the healing spring, and went looking for lunch.

The area around Kiyomizu-dera has its share of shops selling tourist junk, but is otherwise great fun. We took the edge off our hunger with a skewer of grilled balls of octopus from a man just below the temple, making and selling them in a stand just in front of the trailer where he lived. The trailer, and everything else on that side of the street, was precariously close to tumbling down the steep hillside beyond. We went down a side street on the other side and discovered a tiny place, beautifully decorated in blond wood. (Here is the location in Google Maps ) The old lady who ran it had a set menu of salad, bread or rice, green tea soba with one of three sauces (we had one which was inscrutable aside from bonito, squash, and pickles), and dessert. Dessert was a scoop of hu ice cream with read bean paste, glutinous flour balls, and some kind of jelly. I highly recommend it.

Flyer from the restaurant near Kiyomizu dera,

coordinates latitude 34°59’43.91”N, longitude 135°46’45.86”E

Back on the street again, we ducked into an antique shop about to slide down the mountain where an old man, a friend of the lady who served us lunch as it turned out, showed us his tatami rooms crammed with china, dolls, Noh masks, and lacquerwork, then we finished our lunch at a tofu shop and restaurant we had seen on the way up with a fixed menu of tofu the consistency of melted cheese stuffed with rice, two blocks of solid tofu, miso soup, and two kinds of pickles, plus a green tea soy milk which was pleasant, but would have been much more so on a hot day.

The next temple, Ginkakuji, was also closed, but only because we arrived about five minutes after closing. Kiyamizu-dera and Ginkajuji are connected by a path through the outskirts of Kyoto called the Philosopher’s Walk, and we strolled along this for some time instead. Near Ginkajuji, the path has many small, overpriced restaurants, and many cats which K––– stopped to pet. The environs turn residential in the middle, and we saw the immaculately kept back gardens of a shrine, and an overgrown lot, the remains of a teahouse: a standing Buddha, surrounded by rubbish, the building with its windows open and paint fading, a little carriage, all rusty, and full of wilted flowers hung by the stairs leading down from the path. K––– said that probably the little old lady who ran it died and no one wanted to continue it. It was a melancholy sight.

K––– wanted to go to the shopping district around Shijo-dori and Kawaramachi-dori, an arcaded stretch of expensive glittering shops. I was naturally less than thrilled, until we turned a block north and found the Nishiki food market, a covered alleyway lined with tiny food shops. Gorgeous food shops! We had a bite to eat in a restaurant along the alley, and bought some mikkan6, and some tofu donuts, but mostly just walked up and down and salivated.

2009-2-28

We set out early the next morning for the Heian shrine, got lost on the way, and still arrived early enough where the attendants in gi and hakama were raking the gravel and no one but the gardeners were abroad in the gardens behind. Our savior in our confusion was a professor of English poetry at the University of Kyoto, who stopped and offered his assistance, then chatted with us about Switzerland and Austria, where he had been and was going to take his wife this summer, as he led us the few blocks to the shrine.

The courtyard is an expanse of white, carefully raked gravel punctuated by a couple trees. You enter from the south, where a great shinto gate rises some blocks away, and are faced with the intricate wood buildings of white panels and vermilion beams that line the other three sides. The individual buildings aren’t that interesting, but the overall effect is beautiful. We stared for a few minutes, then tiptoed over the newly raked gravel, apologizing to the attendants, to enter the gardens behind.

Four separate gardens wrap around the back of the shrine, from west to east, meant to represent the four major schools of 20th century Japanese garden design. We passed through the ticket booth and stepped out onto a grassy knoll dotted with trees and bushes, a knoll just high enough where we couldn’t quite see what was beyond, just low enough to invite us to climb up and find out. We walked away from the white and vermilion of the entrance, and that is the last we saw of the shrine.

From the knoll we descended into a valley crisscrossed by streamlets, everywhere overhung by trees whose branches splayed into numerous twigs and hung like veils over the paths. Little bridges connected the islands, and a single flowering plum stood out among the bare branches around it. At the edges of the garden, the trees thickened gradually until they were a solid barrier marking the boundaries of the world. At one end of the garden, half hidden by greenery, was one of the first streetcars to operate in Kyoto. Why was it there? I have no idea. At the other, we passed through a vine covered trellis into the second garden.

The second garden looked like a continuation of the first as we passed under the trellis. Then we emerged, and the streamlets of the first garden had become a giant central pond. The boundary was solid, clean, a line of trees, stretching all the way around the pond. A stream led east along the back of the shrine, and we followed it on a serpentine woodland path, until it ended suddenly at the edge of another great pond, again with the boundary fixed and separate, but not an empty expanse of water. In the distance was an forested island with great flat rocks like a giant’s stepping stones leading out to it. It was still, absolutely silent, until a carp’s fin broke the surface and sent ripples across the pond and its lazy splashing sound through the air. As if it were a signal, a figure started setting out the benches covered in red cloth at the small tea house beyond the pond.

From the third garden, we followed another stream to another pond, this one veiled by hanging twigs. The border was indistinct, hidden by bushes and plants on the other side of the path. We caught glimpses of a wooden bridge facing us across the pond as we walked, until we came, like a shock, to a gap: the bridge in full profile with a mountain centered exactly behind it, and just in range of the drifting scent of a flowering plum.

We strolled on, and sat down in the wooden bridge to watch the sunlight dappling its beams and the white side of the palace on the far side. I left K––– here and went back to the beginning to start again. These gardens are meant to be strolled, slowly. The individual views are beautiful, but in slow, steady motion there are heart rending moments: first coming over the knoll from the palace; the first glimpse of the pond in the second garden as I emerged from the primordial mix of tree and ground and water of the first; an instant of aesthetic glory as the stones leading to the island in the third garden come into profile while I strolled along the north bank. And yet I felt like an alien, come to appreciate an exotic experience. The gardens don’t enfold and cradle the visitor like the other Japanese gardens I’ve known.

At last I returned and let K–––, now a little bored, escape. We bought food in the Nishiki market, and had a picnic in the grounds of the Imperial Palace, which are now a public park. We ate our pickles, tuna maki, rice with whole red beans, mochi, sweetened and pickled kidney beans, a salad of the sheets skimmed off of settling tofu, tofu donuts, and mochi two benches down from a Japanese family eating McDonalds, then made our way south to Tofukuji.

Tofukuji is a zen temple in the south of Kyoto. We made it part of the way there, and found a map showing the rest of the way. And here I must protest: north was down, mostly. It was oriented so that up was in the direction you were facing, instead of along a cardinal direction. Is someone in Kyoto’s department of tourism trying to confuse the tourists and get them lost in the backwaters of the city? As K––– commented, “don’t worry until you hear dueling kotos.”

At last we caught our first glimpse of Tofukuji. We stepped onto a wooden bridge over a green stream valley bathed in gold from the afternoon sun, and looked up to another wooden bridge against the blue sky.

We walked on and entered the grounds of the temple, with its giant pavilions in black and white.

We paid our admission to enter the gardens, an expanse of tree dotted moss spreading to the stream valley and the upper and lower wooden bridges.

Stairs led down to a landing and a stone bridge over the stream, then up on the far side to a octogon pavilion containing a Buddha. Covered stairs led up to the zen garden

We passed through its gate, and looked up an irregular stone path leading to an altar. To the right were low shrubs and water leading up a small hill to where the woods started, and to the left, a single tree over raked gravel.

We followed the path up to the shrine, then to the side to join a fair number of people seated on the benches on the left to contemplate the garden in silence. It was magical.

And in walked a loud Japanese family: Papa, with a little mustache and big, thick rimmed glasses, awkward in heavy, clomping shoes; mama, heavyset and well dressed; their daughter, fashionably dressed, tall and thin, pretty and spoiled. Mama leapt over a rope, talking all the while, to stand amid the plants the beside the path while her daughter photographed her. Papa clomped up to the shrine, dropped in a coin, bowed, peered through the grill, turned, and started shouting to the other two. They all came over to the benches on the left and sat. Mama kept talking. Papa kept clomping his shoes. Everyone else eyed each other in alarm, and the garden emptied, including us. It’s pretty bad when you drive the gaijin out.

We poked around the rest of the grounds, including the giant lavatory next to the meditation hall. Apparently collecting the shit of monks seeking enlightenment, using it to fertilize vegetables, and selling these into the city was an important source of income for most zen temples. K––– was dehydrated, which led to an amusing little drama. None of the vending machines were plugged in, so she went and asked the little old ladies at the admission desk where she can get some water. They came flapping out, tiny and hospitable creatures who came up to my solar plexus. They established with concern that the vending machines were indeed off, flapped back into their office and get her a paper cup, returned, showed her the potable water supply used for the covered winter pond they kept their koi in, then look on with approval as we drank our fill.

Hoping that the family had left and we could get a few more minutes in the zen garden, we went back in at 16h40. Last entrance was 16h30, the garden closed at 17h00, but the other old ladies working at the garden entrance took pity on us and told us to go on back in. We spent a few more minutes in the magical silence of the zen garden, then scurried back out at 16h55.

After a rest and a cup of yuzu tea in the hotel, we went looking for dinner. K––– noticed a place in the basement of a big office building (coordinates latitude 34°59’20.68”N, longitude 135°45’34.26”E). Apparently the best quality is generally in the basement in Japanese cities. We walked into an elaborate wood interior, a corridor leading to the bar and to private rooms, and off in another direction to communal tatami rooms, all full of people. A waitress gave us an English menu and bowed us into two places at the bar, next to an old Japanese man with a giant bowl of sashimi who was delighted in a dour way to see K–––, tall, slim, and auburn haired, sit down next to him. He took a good look, and proceeded to give her mute directions on how best to eat her food from time to time.

As usual in Japanese restaurants, the bar looked in on the kitchen. We were seated across from the head chef. How do I know that he was the head chef? He was dressed in a white smock and paper hat like the rest, but his hat had a bright yellow ribbon and smiley face which proclaimed him “#1 Chef.” K––– ordered sashimi of pickled mackerel, a plate of pickles which she graciously shared with me, and raw scallops. I started with a nigiri with salmon flakes, mixed tempura, tuna sashimi, then called the waitress, by means of one of the electronic bells placed along the bar, and ordered a grilled cuttlefish, served with ginger and homemade mayonnaise, and an omelette with minced daikon.

At the end K––– had to find out what the dessert described as a “bamboo charcoal cake” was. It came, served with sesame ice cream. It was black. It was delicious, not too sweet, with a coarse texture and earthy flavor. I have no idea what it was or how to make it. We paid about ¥2800 a person for the meal, but it was one of the best we had in Kyoto.

Interestingly, the restaurant’s card had one of the ubiquitous square bar codes. These are everywhere, on bus schedules, on menus, even on the placards of trees and works of art. Photograph them with a Japanese cellphone, and it opens a webpage, typically the bus schedule, the restaurant’s website, or some information about the tree.

2009-3-1

We passed our morning in two Shinto shrines in the north of the city. We admired Shimogamo around the attendants raking the gravel, until a column of cub scouts arrived, marching in precise line, followed by a longer line of their parents and minders in brown uniforms. We fled into the neighboring park, and found the abandoned wooden shrine to the parents of the Imperial lackey deified in Shimogamo. We paused to enjoy the open field where parents brought their children to play in front of Kamigamo, and spared a sympathetic look for the skittish and unhappy white horse in its box stall near the entrance, a steed for the god. We admired the buildings in Kamigamo. I looked doubtfully at the procession of Shinto priests in white robes, shapeless, black hats, and shoes shaped like boats. Then we wandered down a side path through the woods, past a great oak tree hemmed in by plain wooden buildings, and climbed stone stairs to the most moving object of the morning: the simplest of shrines, plain wood under a tin roof but with every surface covered with prayers on folded and knotted pieces of paper, left by the inhabitants of the run-down residential neighborhood beyond.

Kyoto is lousy with temples and shrines, and while some are beautiful beyond description, most are just another shrine.

The afternoon we devoted to Kyoto’s botanical gardens. March is too early for much to be in bloom except the plums, and the hothouse of forced flowers erected near the entrance. We processed through this hothouse with the crowd of incessantly photographing old Japanese through air so perfumed by blossoms it made my eyes roll back in my head. After we emerged, K––– installed herself on a bench and indulged me as I shuffled around, examining and comparing the morphologies of their many species of bamboo.

We wandered through the stylized Western gardens, then west along an avenue lined with enormous trees. The center of the garden, just north of the avenue, is a grassy field, full of picnickers on this sunny day. Children ran and rolled on the grass, then returned to their parents and grandparents to be brushed off and sent out to do it again. Young couples cuddled on blankets, until a cold wind suddenly picked up, flipped up the girls’ short skirts (Japanese females generally show a lot more leg than in the west), and left a lot of very unhappy expressions.

We passed by the conservatory, since it required a separate admission, and into the flowering plums and the Japanese scattered through the cloud of blossoms, photographing enthusiastically. The plum orchards end abruptly in a wood of enormous conifers, with nothing but a gravel path to soften the distinction, and in this wood we watched a male heron bringing twigs back to its mate to build their nest. Then closing time arrived, and we joined the mass exodus onto the subway.

For dinner we returned to the little okonomiyaki restaurant we found the first night, and were greeted like long lost children by the couple who run it, and by the same regular who was growing out of the bar. It is very much a neighborhood affair. The regulars all address the lady as “okaza” (mom), and she uses the diminutive suffix -chan to them all. We ordered okonomiyaki and yakisoba, both with squid (the yakisoba is good, but stick with the okonomiyaki which is superb), but they fed us little tofu salads and handmade nigiri while our food was cooking, and showered us with questions. Okaza made us origami as a souvenir when she found that it was our last night.

After we had talked and companionably watched baseball for an hour or so, K––– decided she wanted sake. She asked for it, expecting the typical thimble sized glass and small ceramic bottle, and her eyes grew wide when the man simply presented her with the 300mL bottle — apparently the good stuff — and an egg from the oden pot to go with it. In the end we reluctantly decided we needed to get to sleep, and asked for the bill. The man scratched his head for a moment, and scribbled a number on a piece of paper: ¥2200. We were utterly shocked.

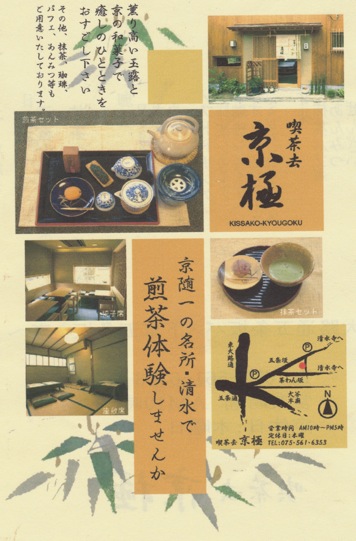

2009-3-2

I was disinclined to emerge from my warm futon the next morning, but K––– spread bait for me (chocolate and strawberries) just beyond my pillow, and I emerged far enough to snap them up and decide that perhaps it was time to get up. We had decided to try the breakfast in the hotel, served in a communal room downstairs from 7h30 to 9h00. We ordered the night before, not actually choosing what we would eat, just that we would eat, and descended to find a tray waiting with cooked salmon, an omelette, and five kinds of pickles. Then a waitress scurried up with miso soup, tea, and a lacquer box of rice. After starting the day with granola bars for the past few mornings, I had forgotten just how good the Japanese idea of breakfast makes my stomach feel.

K––– had to leave just after lunch to return to work, so we walked north to the Nishiki market again, bought snacks and sweets to carry back to our coworkers, hers near Tokyo, mine in Switzerland. In strolling, K––– noticed a ¥1200 set menu at a place called the Black Bean Cafe: two kinds of tofu (white and black bean), natto tempura served with rice, tiny, dried fish eaten whole, rice with black beans, miso soup, sweetened black beans, and a tiny cup of black bean sake.

For my part, I was charmed by the model of the shop on top of the display case.

The downstairs is a shop where they sell the same products served in the restaurant upstairs. We left our shoes in a glass case by the stairs, and ascended into the beautiful room above.

The set meal also comes with dessert, and that is where those large stone contraptions on the tables come in. They’re grinders. The dessert, usually something sticky like dango, comes with a little bowl of hull-on soybeans, a strainer, and a brush. The waitress carefully instructed us to put the soybeans –– three at a time! –– into the hole on the top, turn the wooden handle, and use the brush to collect the resulting powder in the bowl. Then we sprinkled this through the strainer over our dessert like a less sweet version of powdered sugar.

I saw K––– off at the station, then returned to photograph the market, and fill myself with tofu donuts and appallingly beautiful mochi in the process.

|

| Nishiki Market, Kyoto |

Once I finished with the market, I fetched my bags where I had left them at the inn, and set out for Shunkoin temple, where I would be staying my last couple of nights in Kyoto. Shunkoin is part of the enormous Myoshin complex of zen temples to the west of Kyoto, beautiful, peaceful, and surrounded by residential areas. It’s part of the neighborhood, open day any night. The locals wander through on their way from place to place, and send their children to an elementary school in one of the temple buildings just inside the north entrance.

I asked directions of a jolly monk loading bags in the back of a car, and finally found the main gate. It was closed. This stopped me cold for a minute until I realized there was a small door off to the side that was unlocked. I shuffled around inside for a little while before an old monk greeted me, and sent for the vice abbot.

The vice abbot takes care of all guests. Shunkoin offers meditation classes, particularly to westerners, and he is central to this scheme. He studied in the USA and speaks English as though he were born in California. My room was spartan: a carpeted floor with a futon on a heating pad; a desk and a few books; and a wireless hub. The toilets are outside, through the next gate in the temple. The shower is thankfully enclosed and heated. I bought a bento from the local convenient store, and settled in to rest after the whirlwind of sightseeing with K–––.

2009-3-3

I had an appointment to see the Imperial Palace the next morning. The grounds of the palace are now the public park in the center of Kyoto, but the palace itself remains closed. Visitors can see it for free, on a tour by appointment. I presented myself shortly before my appointment and showed my permit to the guards at the northwest (servants’) entrance. They sent me in to a reception desk, where I was sent to a heated waiting room, where I gratefully recovered from the chill wind blowing outside. The rest of the tour filtered in, we were shown a ten minute video about the palace, then followed a cute Japanese lady out into the cold to listen to her spiel, delivered in flowery English in an indulgent tone usually directed at schoolchildren. We were followed the whole time by a grim man in a dark suit holding an umbrella behind him like a swagger stick, ready to cane anyone who fell too far behind.

The emperor and empress have nothing to do with this palace anymore, but the tour still only goes around the outside. We were not permitted to see the buildings and garden of the empress’s quarters, nor inside of the palace itself. In the end, the most interesting part were all the architectural details: buildings with roofs made of layer upon layer of bark held together by bamboo nails, which have to be replaced every twenty five years if they don’t burst into flame before then; the white ends of the room beams, ubiquitous in Japan, which we were told were originally painted with crushed seashell to stave off termites, but then became traditional; the regular cycle of the whole thing burning to the ground and being rebuilt, most recently in 1958. Most of the place is in an archaic style with plain wooden floors, no tatami, no shoji, and utterly uncomfortable. And we saw the Imperial hackysack court, which apparently was the official court ballgame.

The emperor is one of the weird cultural artifacts like ikebana that the older generation of Japanese wields against the young. Their reverence for him is pathological, not the healthy and indulgent affection of the Danes. The imperial palace is an attempt to scale up the brilliance of Japanese domestic architecture, and in the process completely defeats its charm. To anyone familiar with the castles and palaces of Europe, it feels like a ludicrously large wigwam.

We were permitted to see the emperor’s personal garden, across from the hackysack court. A streamlet nestled among tiny hillocks runs into a pond from the north. The hackysack court adjoins a pebble beach in a miniature cove. Stone bridges sprout from the cove’s headlands to connect the pond’s islands to the shore. I would have lingered and explored, but we were chivvied along, and I very quickly found myself back outside the northwest (servants’) entrance and ready for lunch.

I found lunch in a restaurant paneled in black, painted wood just south of Nishiki market. It was a sizable place with a long bar lined with giant sake bottles, roughly fifteen tables, and two tables on tatami at the back. And a giant woodblock print of a fish on the back wall. A waitress in an old style apron and headcloth presented me with a menu, which I mostly failed to decipher and stubbornly ordered from anyway. What I got was cold green tea soba, two pieces of tuna sashimi, a couple pieces of vegetable and oyster tempura, and some pickles. It was excellent, and almost what I expected. Then I went into the market itself, finished my lunch with fresh tofu donuts, and bought food for my dinner: more tuna sashimi, more of the salad of tofu skimmings, black bean rice, mochi, an omelette with mushrooms, carrots, and parseley, and more of the sweetened and pickled black beans we ate at the Black Bean Cafe yesterday.

By this time it was half snowing, half raining, but I took 12 bus to Kinkajuji as planned. Almost. I got off too early, at Kenkun shrine in Funaokayama park on a hill at the edge of the city, and was glad I did. The park was utterly empty in the rain, except for the gate keeper who told me that it was open, go on up, and watched me climb the stone stairs as if I were insane. Up the stairs, along wooded paths, and I came upon a tiny Shinto shrine on the end of a ridgeline overlooking the city. It looked like the fairy tale ideal of a mountain shrine. There was almost nothing there, just one or two pavilions, but the tiny space amid the woods and the vista out over the city in its valley was stunning. At last I emerged from the park, not having seen another soul for forty minutes, and came at last to Kinkajuji, where I saw the bus dropping everyone else off at the entrance.

UNESCO has been free with its favors in handing out ‘world heritage site’ designations in Kyoto, but Kinkajuji deserves it. I turned a corner in the path, and came suddenly upon a pond, and across it, the golden pavilion. It stole my breath, even in the rain. Perhaps especially in the rain.

The first glimpse of the golden pavilion

Everyone stopped here, and the sole guard, a jolly old man, spent his time being asked by schoolgirls to take pictures of them in front of the pavillion. At last I tore myself away, and wound around the pond to see the pavilion up close.

The path turned up into the woods, past a waterfall shattering on a rock,

then opened onto an upper pond surrounded by forest on all sides. The only human touch was a single island with a stone lantern.

It was empty, silent. Then about forty ducks suddenly came roaring out of the woods in a group, landed on the pond, and immediately set about looking as if they had been there all the time. The path wound past three gift shops during this time, and finally arrived at two more, a tea house, and a shrine with change machines next to it in case you weren’t carrying just the right denomination to give to the god.

2009-3-4

I was to leave for Tokyo the next day, but first I had one more appointment. I registered for it at the same time as my tour of the Imperial Palace, and the palace was definitely secondary. I crept out of the temple in the early morning, caught the 91 bus to the Hankyu line to Katsura, and caught the bus from there to Katsura-Rikyu, the Katsura Imperial Villa. I got off, and tried to reassure the driver, who was making sure in vehement Japanese that I knew how to get to the entrance to the villa from the bus stop.